Speaking in a foreign language is not easy for students; and teaching speaking is not easy for us as teachers. But here’s the thing: every teacher is also a learner at their core. We’ve all felt that moment of freezing up, of having words in our head but struggling to get them out. And yet, not everyone experiences it in the same way or at the same time — some people jump right in and speak freely, while others — who might even know more English — hesitate or avoid speaking altogether.

To answer that, we need to look at what speaking really is, and why it can feel so mentally demanding. In this article, you will learn more about the stages of speech production, cognitive load theory, the sociocognitive load, and some practical tips on how to help our brain.

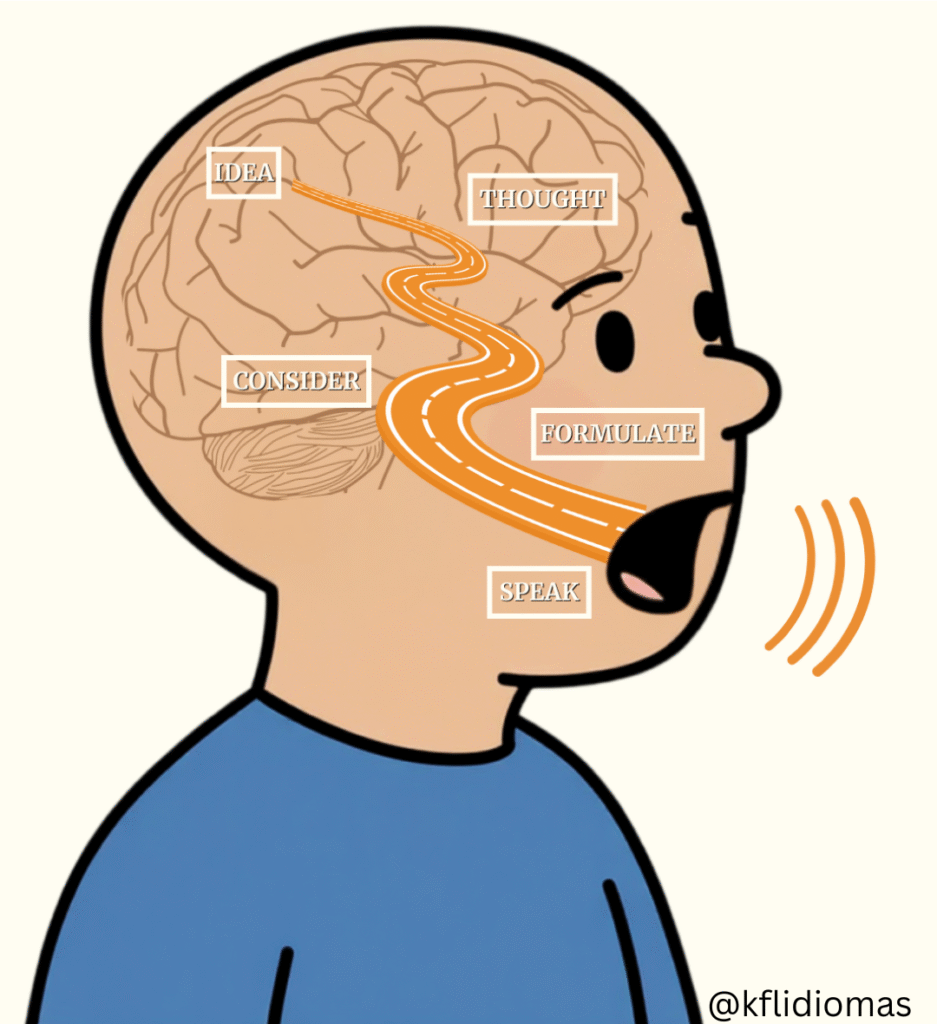

Speaking is undoubtedly a challenging skill to master, not only for the speed involved, but also for all the mental processing that needs to happen. After all, there is a long, winding road that connects our brain to our mouth – so to speak.

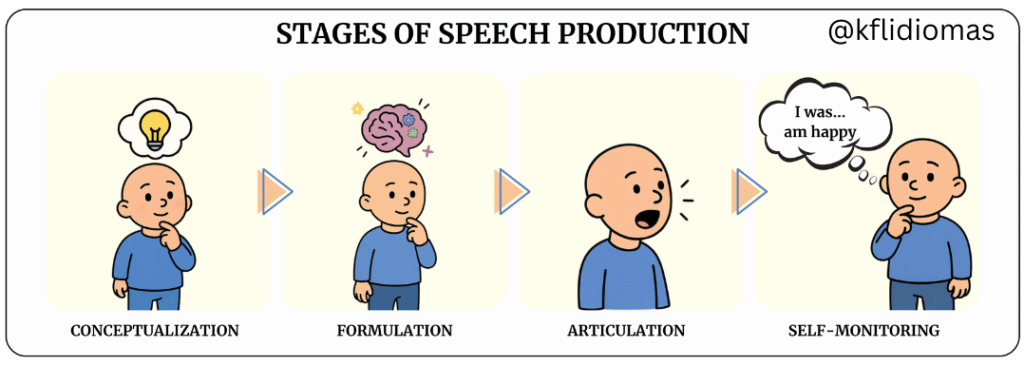

Whenever we verbalize something, a complex cognitive process happens. First, we generate the idea, conceptualization. Then, we select words, grammatical structures and phonological rules to express what we thought. That’s the formulation. Later, we come to physically articulate the sounds of what we had chosen. Finally, we might self-monitor to find mistakes during or after speaking. These are the stages of speech production described by Levelt (1989), a foundational model in psycholinguistics. Overload at any of these stages can disrupt timing and accuracy — two core challenges in spoken production.

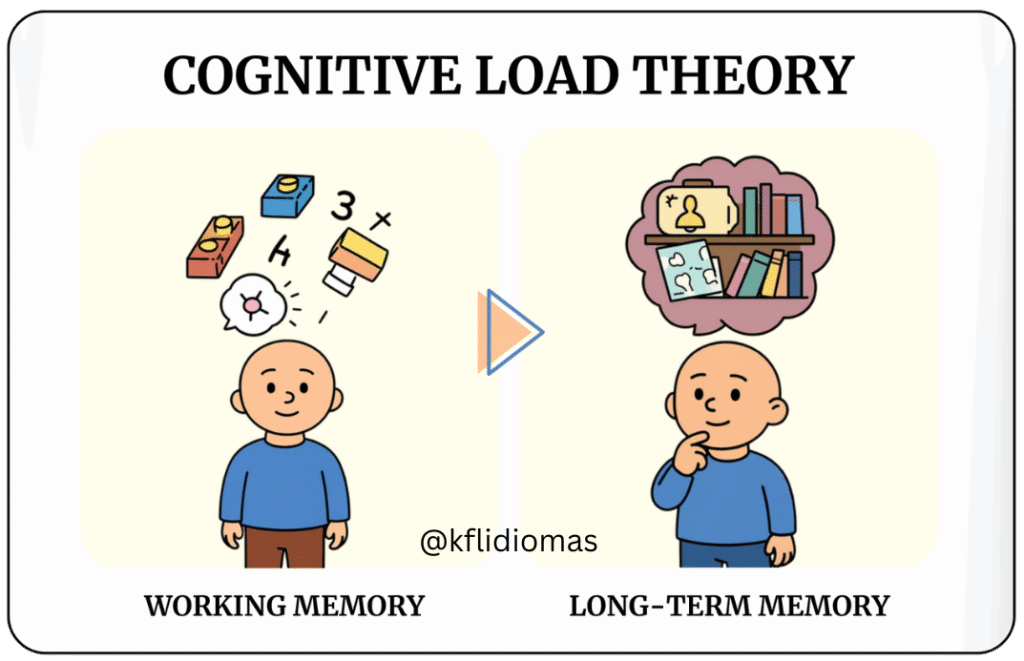

This foundational model leads us to the complementary cognitive load theory. To understand the mental strain of speaking, we need to distinguish between two types of memory: our working memory, which is a limited-capacity system that temporarily holds and processes information; and our long-term memory, an unlimited system that stores all of our knowledge. What learners essentially need to do is to get information from the working memory to be stored in the long-term memory. Easy as pie, right? Not so much, perhaps. But it’s absolutely doable.

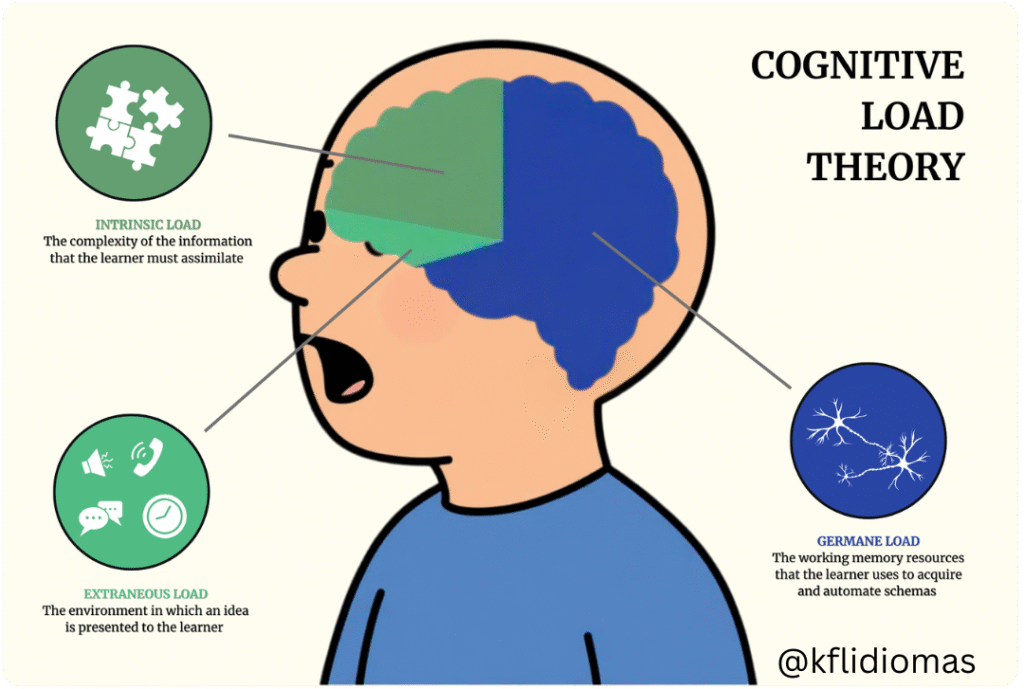

Our working memory is influenced by two additional components: the extraneous load, which may be anything that hinders learning, – from wordy instructions and topic unfamiliarity to anxiety or distractions; and the intrinsic load, the inherent complexity of a task, for instance using all the narrative tenses accurately.

To improve speaking, learners must engage in what is known as germane load — the mental effort involved in processing and organizing new information. This means actively building connections between what we already know and what we’re learning, then refining those connections through deliberate practice and meaningful use. That’s how we move toward automaticity, which is what will help us develop spoken fluency.

And yet, even if we understand the different types of cognitive load, something is still missing: the social aspect of speaking. Thus, Gianfranco Conti (2025) highlights the importance of the sociocognitive load. He points out that the social pressure of being watched, the fear of making mistakes, or the emotional freeze of anxiety can all add to the mental strain. Even practical issues — like unclear steps, cluttered visuals, or too much input at once — can quickly overload working memory (Edutopia, 2022).

Understanding the mental architecture behind speaking is the first step. But what truly matters for us is knowing how to navigate this complexity, whether for ourselves or with our learners. So, how can we reduce unnecessary load, make room for meaningful processing, and turn speaking into a more manageable task — and rewarding experience? Here are some strategies to address just that.

A) To reduce extraneous load:

- Start with familiar topics and experiment with recording yourself for 1-2-3 minutes, focusing more and more on advanced language.

- Look for safe learning environments to reduce anxiety. Pair this with self-regulation tools – a quick breathing pause, a grounding object, or positive self-talk to free up mental space, so you focus on language instead of anxiety.

- Use clear models, like example dialogues, sentence starters, and linking words to provide support to the learning process and help level up speaking.

As you implement these strategies, you’ll also benefit from exploring practical speaking strategies that reduce cognitive overload(5 Speaking Secrets article).

B) To manage intrinsic load:

Simple response frameworks also work as safety nets. The PREP method, (Point, Reason, Example, Point again) or the “Rule of 3,” help reduce planning load and keep fluency going. And don’t underestimate small regulation tricks: steady breathing, grounding oneself with an object, or even keeping our hands busy can prevent freezing (Edutopia, 2025).

- Focus on one function at a time. For example, starting with comparing, then moving onto hypothesizing, etc

- Select three chunks of language (idioms, fixed expressions, sentence frames) you want to work with and insert them into speaking tasks.

- Start comfortably, then gradually increase task complexity to build confidence and perform better.

As Conti (2025) reminds us, it’s not usually one single challenge that causes breakdowns — it’s the pile-up: grammar, accuracy, instructions, and social pressure hitting at once. So, keep steps clear and simple, but vary your practice so you face realistic pressures.

C) To increase germane load:

- Use and abuse task repetition with incremental changes to maintain appropriate levels of challenge.

- Include task variation to recycle language in different meaningful ways while building fluency, for example, after telling a story, re-tell it with a new ending. When you pair this with active reading practices that strengthen comprehension and critical thinking, you create multiple neural pathways that reinforce both skills simultaneously.

- If you want to build automaticity, work on a variety of shadowing techniques.

Pair this with emotional safety and regulation tools. A quick breathing pause, a grounding object, or positive self-talk can free up mental space, so you focus on language instead of anxiety.

And here’s my two cents: have your students reflect on their process. Ask them: what did they struggle with? What did they improve? Reflective questions like these — ideally in conversation with a teacher — can guide you toward new techniques and better results.

Next time your mind goes blank, remember this: it’s not that you can’t speak — it’s that your brain is juggling too many loads at once. Lighten the load, focus on what matters, and fluency will follow.

So, whether you see yourself as a teacher, a learner, or both — remember that speaking challenges unite us. Every hesitation, every pause, is not a failure but part of the shared journey we’re all on as learners at our core.

Now I’d love to hear from both sides: learners, what part of speaking feels most mentally demanding for you? Teachers, what strategies have helped your students find their voice? After all, we’re all on the same path — teachers learning as they teach, learners teaching as they learn.

2 Responses